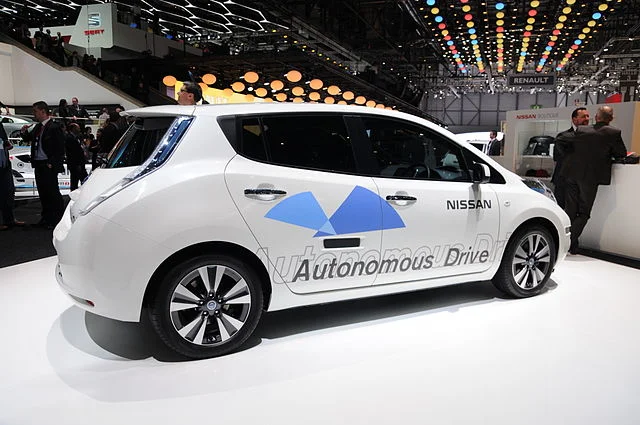

Driverless cars are on the road now – Google’s fleet has logged about 700,000 miles of autonomous driving – and the California DMV will be issuing regulations in a matter of weeks allowing self-driving cars to be sold to the public, possibly setting the regulatory pattern for the rest of the country (video). Google has predicted 2017 for first commercial availability, while Nissan and Mercedes say it will be 2020. The cars are highly complex systems whose sheer quantity of software surely exceeds the hundred million lines of source code in today’s non-autonomous vehicles. They weigh thousands of pounds and hurtle down public roads – robots with human payloads. But how will we know they’re safe?

Google’s answer at DMV workshops in March 2014 and May 2013 was, essentially, “trust us” (video, video, video). The company’s representative, Ron Medford, said Google would “self-certify” the car’s roadworthiness and then the DMV could take it for a test drive (video) akin to what a human driver undergoes today (video, video, video, video). “That the company … [is] ready to submit its vehicle for [DMV] testing is kind of the proof that it’s ready,” he said, and argued against any more detailed scrutiny than that (video, video).

This is the same Google that so betrayed customers’ trust that it’s under twenty years of outside privacy monitoring, imposed by a consent decree which it later allegedly violated (leading to a record multi-million dollar settlement). Yet the company’s answer is to supplement “trust us” with nothing more than a simple road test – even though computer experts agree that such testing is no way to verify safety-critical software.

A Chrysler representative, Steve Siko, also endorsed self-certification (video). “It’s not like any manufacturer is trying to skirt around some safety rules,” said another Chrysler rep, Ross Good (video). From VW, Barbara Wendling also sang the self-certification tune (video), and said she had “no worries that anybody in the industry is going to put an unsafe product into California or any other state” (video).

Really?

That comment ignores GM’s defective ignition switch that may have killed 309 people (the company says it’s 13) – almost 15 million vehicles recalled to-date amid criminal probes and possible cover-ups – and Toyota’s deadly accelerator pedals (89 fatalities, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration), to name only two of the unsafe products automakers have in fact put on the market in recent years.

Nevada accepted Google’s “trust us” gambit (pdf, p. 13) but like that state’s slot machines, it’s a bad bet. Google’s approach is not good enough, because the tech company and automakers have already demonstrated they’re not trustworthy and because experts acknowledge that complex software can’t be adequately verified simply by testing it. That’s especially true of safety-critical hard real-time systems. “Hard” means that the system must respond in timely fashion to avoid devastating consequences, like an automobile crash.

Indeed, a mere “road test” is not how validation works in other safety-critical applications like medical device software or avionics hardware and software.

The Right Way to Validate Software

As the Food and Drug Administration says, “Typically, testing alone cannot fully verify that software is complete and correct. In addition to testing, other verification techniques and a structured and documented development process should be combined to ensure a comprehensive validation approach. Except for the simplest of programs, software cannot be exhaustively tested. Generally it is not feasible to test a software product with all possible inputs, nor is it possible to test all possible data processing paths that can occur during program execution.”

And who should do the verifying? The FDA addresses this too: “Validation activities should be conducted using the basic quality assurance precept of ‘independence of review.’ Self-validation is extremely difficult. When possible, an independent evaluation is always better, especially for higher risk applications.”

Not surprisingly, the agency requires pre-market submission of very detailed flowcharts, design documents and the like (apparently including source code) for devices that present a risk of death or major injury.

Avionics is even more stringent. In the U.S., knowledgeable reviewers called Designated Engineering Representatives or DERs are certified and appointed by the Federal Aviation Administration. Some DERs (Consultant DERs) are independent contractors while others, although they work for the manufacturers (Company DERs), are part of a culture where they are deemed to owe their loyalty to the FAA rather than their employers; in fact, DERs are appointed to represent the FAA and are legally required to maintain objectivity (pdf, p. 21). Europe uses outside testing labs.

In both jurisdictions, detailed documents govern the certification of in-the-air avionics software and hardware (in particular, custom devices like FPGAs, PLDs and ASICs) as well as ground-based avionics software. Test plans, source code, design documents and more are required to be submitted, and the programming process itself has to meet certain standards. Every line of safety-critical software code has to be justified – traced back to its rationale – and has to be executed during testing.

The difficulty with the avionics approach is that it enormously increases costs and product development time. In the automotive sphere, that would mean people continuing to die from human-caused accidents – which is about 95% of the annual 32,000 fatal accidents today (pdf, see pp. 24-25) – while we waited for (hopefully-safer) driverless cars to emerge from testing. It’s a real issue, but there has to be some compromise between “trust us” and hyper-punctilious verification.

You don’t have to be a high-tech expert to understand the concept. Self-certification is not even the way it works when you want to add a roof deck to your house. At least in urban areas, you have to show your plans to the city or county building department first (and the plans are usually drawn up by an architect or engineer who passed a state licensing exam; not so with software). There’s a physical inspection after the deck is built.

Google wants to skip the first step and jump to the second, but why should we regulate robocars less rigorously than roof decks?

Certification of driverless car software and hardware by an independent testing company, coupled with DMV review and multiple test drives, is the best way to give the public confidence that these cars are as safe as can be. I’m well aware – as a former programmer and as a lawyer who has represented software vendors – that source code is sensitive. But so is public safety. Ultimately, meaningful certification will be good for the driverless car industry as well as for the public.

At the DMV sessions, a Bosch representative named Soeren Kammel endorsed third-party certification and re-certification when a product is updated (video, video). A consumer advocate, John Simpson of Consumer Watchdog, focused on privacy issues (video), which are also critical, but he didn’t explore certification.

Google declined to comment for this article and the DMV told me the issue would be “addressed in the regulations when we release them … later this summer.” They’re writing the regulations now: you can weigh in by clicking here to email the DMV (and cc me).

Bugs are Inevitable

Bear in mind, there will be bugs in the software and flaws in the hardware, as even Google admits (“should it fail .. we want to reduce the impact”; “there will be some failures,” video). That’s the nature of electronic hardware and especially of software: we’ve been designing and building physical structures for thousands of years – bridges, for instance, for 3300 years – whereas even the term “software engineering” is less than 50 years old and the actual discipline of rigorous programming, in any meaningful sense, is younger still.

As the FDA says, “because of its complexity, the development process for software should be even more tightly controlled than for hardware, in order to prevent problems that cannot be easily detected later in the development process.” (They put that in bold, not me.)

Programming is still a dicey business, in other words, as is obvious to anyone with a smartphone that crashes, overheats or drains its battery without reason. (And that’s not to mention the prospect of your phone being hacked.) I have just such a phone, a Samsung Galaxy S4, which initially worked quite well. Now, not so well. It runs on Android software written by Google.

Google engineers and programmers are smart, but they can’t escape humankind’s collective immaturity of knowledge around the task of engineering software that is safe, reliable, error free and resistant to malicious attack. These cars will kill people, albeit hopefully many fewer than the number of people killed today by human drivers.

And sometimes when they do maim or kill, the cars will have to make ethical decisions: if three pedestrians dash across the road one after the other right in front of a car, should the car jam on the brakes knowing it will hit and kill two of them, or should it swerve and kill only the third one instead? In the latter case, fewer lives will be lost but the pedestrian it kills wouldn’t have died had the car not affirmatively decided to swerve. Passively kill two people or deliberately kill a different person? Kill one pedestrian or swerve into another car and perhaps only injure its occupants?

There are many variants of this so-called “trolley problem” and the car’s software will have to make hard choices. These are moral dilemmas that society – government regulators – should at least have input into. They’re not decisions that Google programmers should make alone at their white boards.

Those programmers and their colleagues – engineers, designers, businesspeople and others – are brilliant, and they appear to have the most ambitious goals – and be the furthest along – of any company working on autonomous cars. Google has brought the world some great products, and a commercially available self-driving car, although it will bring enormous dislocations, will bring enormous benefits (pdf) as well, if it’s safe.

Why Google and Automakers Can't be Trusted

Notwithstanding Google’s old “don’t be evil” motto, the company has overreached and been slapped for it just like any other large company. In 2010, it deployed privacy-busting features in Google Buzz, which resulted in the FTC imposing an astonishing twenty years of outside privacy audits starting in 2011. Yet the following year, Google allegedly violated that already-unprecedented consent decree and ended up paying a record $22.5 million settlement. And in 2008-2010, the company made an allegedly “intentional mistake“ by sniffing personal data from WiFi routers as its cars photographed the streets, and then apparently attempted to conceal this breach of people’s privacy. The FCC fined Google $25,000 for impeding its investigation.

Google is a great company, but it’s a big company, and there isn’t a day since the era of 19th century robber barons that big companies haven’t overstepped and run roughshod, absent determined regulation.

Like most large companies, Google aggressively looks after its own interests even at the consumer’s expense. That makes “self-certify” a pretty thin answer when it comes to Google car safety – or, for that matter, privacy, since driverless cars are “data guzzlers” that will be acquiring 30 to 130 MB of external visual and other sensor data per second when in operation. (Even now, the race to control the dashboard is on.) And that’s not to mention the GPS data associated with the passengers (i.e., Google will know where you go in the physical world, not just on the Internet) and the likely cameras inside the vehicles, at least for those owned by rideshare services such as Uber, in which Google invested over a quarter-billion dollars last year.

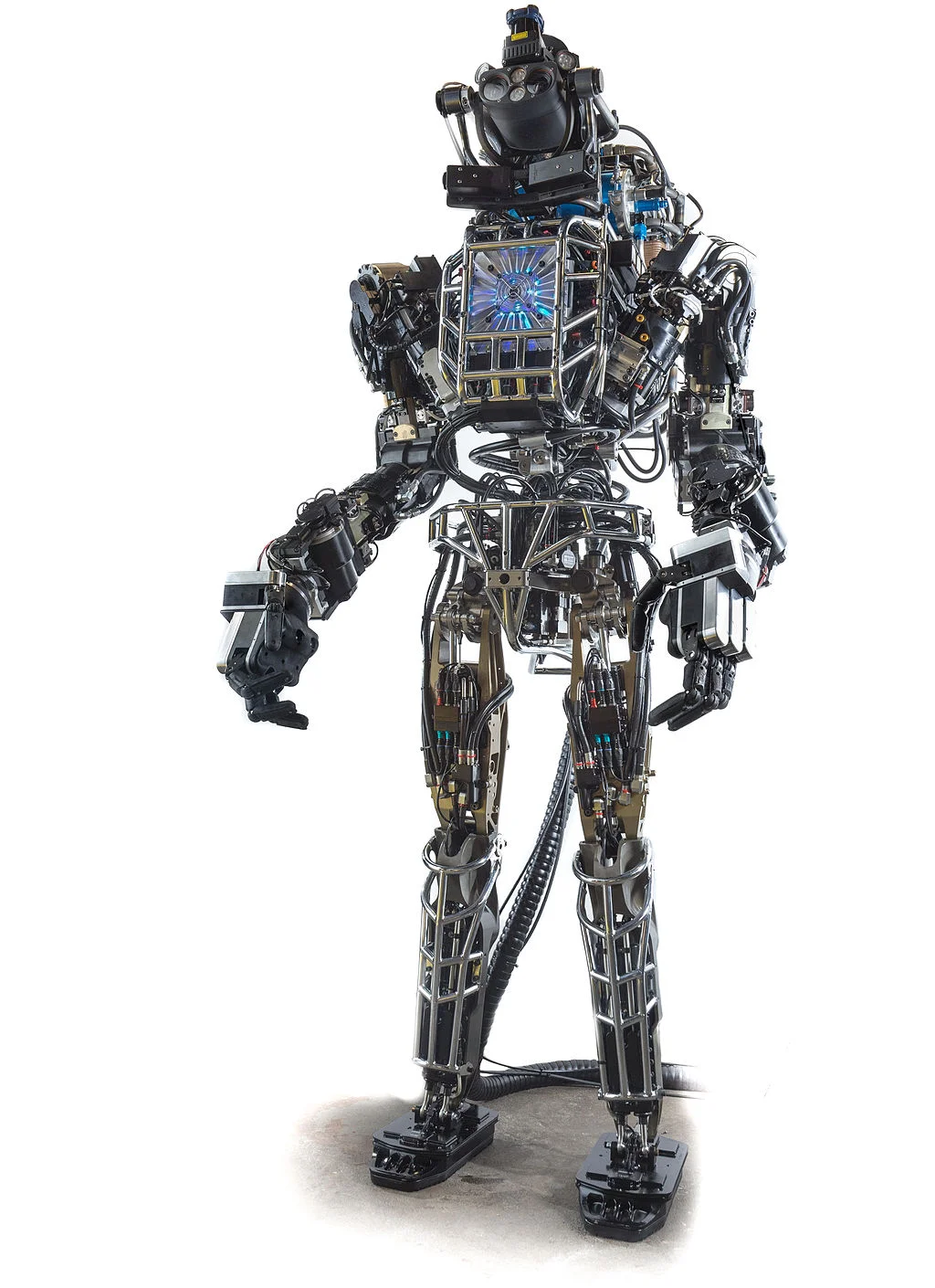

That Uber deal is no outlier. As the Internet morphs into the Internet of Things, the company is transforming itself from an Internet giant into an enterprise with access to – and control over – the physical world. In the last seven months, Google has bought both the smart-device maker Nest and seven robotics companies including Boston Dynamics, which makes robots than can gallop at 28 mph or carry heavy payloads. One of them is even in humanoid form. Six feet tall and weighing 330 lbs., it looks like the Terminator, minus the skin. So while Google’s newest driverless cars – which omit steering wheel and pedals – were deliberately designed to look “friendly” and “cute,” this is not your father’s Google.

And Google, of course, is not the only company developing driverless cars. It's an industry-wide project, yet many automakers have an appalling disrespect for public safety: they fought seat belts, set private detectives to harass and intimidate consumer advocate Ralph Nader, and lobbied against air bags for years, delaying a mandate until 1998.

Meanwhile, also in the 1990’s, over 200 people died in crashes linked to failure of Firestone tires, but they weren’t recalled until 2000. Consumer advocates charged that both Firestone and Ford (in whose vehicles a majority of the deaths occurred) covered up the problem and failed to inform NHTSA.

Present-day behavior is no better: In March of this year, Toyota agreed to pay a record $1.2 billion criminal penalty stemming from charges that it intentionally hid information about safety defects from the public and made deceptive statements to protect its brand image. That was in addition to an earlier $48.8 million civil penalty and a litigation settlement of over a billion dollars. All were in connection with unintended acceleration: ultimately, in two separate recalls in 2009 and 2010 totaling nearly 8 million vehicles Toyota acknowledged that its gas pedals could get trapped under floor mats or that the pedals themselves could simply stick, leading to out of control vehicles. Deaths and injury were the result.

Even more ominously for driverless cars, a jury in 2013 found Toyota liable for unintended acceleration stemming from a third cause, alleged software errors. An expert on embedded systems (real-world machinery that incorporates software), Michael Barr, charged that he found 80,000 violations of software reliability programming rules in Toyota’s code (pdf, p. 29), even after an investigation by NASA (on behalf of NHTSA) had found no software cause for unintended acceleration but not ruled out the possibility either (pdf, p. 17; pdf, p. 13); a NASA engineer charged that its team was taken off the investigation prematurely. The jury awarded $3 million in compensation and was set to consider punitive damages when the case settled.

Toyota is not the only automaker with unintended acceleration problems. Just last weekend, NHTSA disclosed that it’s investigating 360,000 Nissan cars for the same problem, in this case allegedly caused by improper design of a trim panel. Last month, Ford recalled 1.4 million vehicles, for defects including loss of power steering and (as with Toyota) floor mats that can interfere with the accelerator.

That followed a recall by Ford of about 700,000 vehicles for software bugs that could cause airbags to delay inflation and – a separate problem on the same vehicles – doors that could come open while the car is moving. Also last month, Chrysler recalled almost 500,000 SUVs because cracks in a circuit board could lead to a faulty signal that caused the transmission to shift by itself from Park into Neutral. Toyota too had a software recall, in 2010, involving anti-lock brake software and another last month, involving airbag electronic control unit software.

Also on the airbag front, chemical and mechanical defects have been disclosed in the last several weeks in airbags from a company called Takata, resulting in recalls or halted sales by eight car companies: Ford, Chrysler, Honda, Mazda, Nissan, Toyota, BMW – and GM, a company which this year has recalled over 28 million cars in about 30 separate recalls.

The most noted of those recalls, of course, have been for an ignition switch problem. In the last five months the company has recalled about 14.8 million vehicles (6.6 million in the last several months plus 8.2 million yesterday) from model years 2003-2011 because the ignition switch can turn off while the car is in motion, disabling the power steering, power brakes and airbags. According to the government, GM knew of the problem since at least November 2009, but didn’t tell NHTSA for almost 4-1/2 years. The New York Times reports that GM’s knowledge goes much further back: a GM engineer approved the faulty design in 2002 before the car was released, even though the part maker said the switch didn’t meet specifications. GM investigated later complaints, but closed the inquiry in 2005 because “none of the solutions represents an acceptable business case.”

Four months later came the first death tied to the ignition switch.

The following year, the same GM engineer allegedly signed off on a redesigned switch intended to be safer, but there was no recall for another eight years. Last year, the engineer claimed under oath in a wrongful death suit that he had not authorized the change (notwithstanding a signed document to the contrary); he told Congressional investigators in May that he didn’t remember.

Also last month, the company paid a record $35 million civil penalty even as the Secretary of Transportation said “what G.M. did was break the law.” According to NHTSA, GM employees were actually trained in how to obscure safety problems. Documents released last week by a Congressional panel reportedly show that a current top GM executive knew of the problem as far back as 2005. Criminal, congressional, SEC and state investigations are ongoing. Hundreds of lawsuits have been filed, and a compensation plan was unveiled yesterday that could cost the company billions.

In addition, a second GM ignition switch problem has emerged: in many of the same cars with switches that could turn off while driving, it was also possible to remove the ignition key while the car wasn’t in Park or while the engine was running. A GM report said that the company knew about this in the early 2000’s but didn’t recall the cars until April of this year. Meanwhile, although NHTSA received the report in April, it wasn’t posted on the agency’s website until a reporter asked for it in June.

These are the sorts of companies that would self-certify their driverless cars.

What About the Regulators?

Not only did NHTSA delay posting the safety report, it seems to have fumbled the GM ignition switch issue from the beginning. The agency received the first complaint in 2003 but didn’t propose an investigation until 2007. Even at that, no recall occurred until 2014. Instead, despite receiving an average of two complaints per month, NHTSA repeatedly responded that “there was not enough evidence of a problem to warrant a safety investigation,” according to the New York Times. Now Congress is investigating NHTSA as well as GM.

NHTSA doesn’t only handle recalls; it’s the federal agency that issues automobile safety rules. Under California’s self-driving car law, any NHTSA regulations on the subject will preempt whatever the DMV is doing now.

Commenting on the agency’s approach to software, embedded systems expert Barr said, “NHTSA … needs to step up on software regulation and oversight. For example, FAA and FDA both have guidelines for safety-critical software design within the systems they oversee. NHTSA has nothing.” (See also pdf, p. 44.) There are techniques to reduce automotive software risks, but NHTSA doesn’t require them.

And the agency is not currently regulating driverless cars at all.

That leaves the field to the less technically-experienced, more resource-poor state DMVs. It’s not hard to play one state off against another, and that looks like what Google did with California. Although a Stanford report says that self-driving cars were “probably legal” already, the company presumably wanted more certainty, so it got Nevada to pass a driverless car law to its liking in 2011, then Florida, and then used those statutes to incite California legislators to act. Sacramento, fearful that Google’s car operation would decamp to the home of legalized gambling, passed legislation requiring the DMV to issue regulations by January 1, 2015, legalizing the cars on California roads. Gov. Jerry Brown signed the bill at Google headquarters in September 2012.

But a section of the law, CVC 38750(d)(2), requires that the regulations include “any testing, equipment, and performance standards ... that the department concludes are necessary to ensure the safe operation of autonomous vehicles on public roads, with or without the presence of a driver inside the vehicle.”

The only way to even have approximate confidence in the safety of a complex embedded system is for a knowledgeable independent third-party certification authority to review (under confidentiality agreement) the software and firmware source code, custom chip (ASIC) designs, hardware specs, design documents, flowcharts, and other technical documentation.

The Problem with Road Testing

If you’re not a programmer, you may still be wondering why road testing is inadequate for driverless cars. Once again, the FDA explains, “One of the most significant features of software is branching, i.e., the ability to execute alternative series of commands, based on differing inputs. This feature is a major contributing factor for another characteristic of software – its complexity. Even short programs can be very complex and difficult to fully understand.”

It is hard enough to test garden variety software (say, Microsoft Word), whose operation is deterministic and does not require sophisticated judgments, involve real-time sensor inputs or perform safety-critical functions. A word processing program is comparatively straightforward, yet MS Word, for instance, still manages to be buggy.

A robocar’s software is non-deterministic, in that (a) it makes high level decisions (brake? accelerate? swerve? turn? etc.) in real time and (b) it does so in response to huge quantities of extremely complex sensory inputs representing dozens or hundreds of stationary and moving objects that are never the same twice. No matter how precisely you try to replicate a road test, something different will always happen:

● One time the sun will glint off the windshield of an opposing car and blind a sensor, perhaps causing the car the mis-steer – or maybe the sun will be at a slightly different angle that day and the problem will remain latent, ready to affect an unwary consumer.

● Maybe a splash of mud mixed with oil and gravel will fly up past the radar in the front bumper, leading the car to swerve away from an imagined obstacle – or maybe the road will be dry that day, or the mix of oil, mud and gravel just different enough that the software properly processes and ignores it.

● Maybe a journey will be long enough and the number of objects encountered large enough that a heavily-used area of memory referred to as the “stack” will overflow, with potentially catastrophic consequences. Stack overflows can be hard to debug or predict. But perhaps the road test will be too short to trigger the bug, again leaving latent a problem that will only show up when a car crashes in real-world operation.

● Perhaps one day the car will pass by a strong electrical field – say, from a power plant or even a downed wire – that evokes an electric current that modifies memory or triggers a false sensor reading, again leading to a dangerous malfunction not detected during a DMV road test.

● How vulnerable are the car’s sensors to snow, ice and mud? A fair-weather road test won’t answer that question – and we already know from the crash of Air France Flight 447 off the coast of Brazil just how deadly the consequences of sensor malfunction can be.

● Maybe one day the car will hit exactly 32 mph – a binary number that looks like this, 100000 – at precisely the same time a car in the next lane is decelerating and hits 16 mph (10000) and that confluence of zeros and velocity changes triggers some quirky bug that only appears if GPS signal is momentarily lost and a train crosses in front of the car. Of course this is a contrived example (here’s one from the real world), but the point is that software can fail for strange reasons in weird and sometimes catastrophic ways.

As the DMV assistant general counsel conducting the driverless car sessions, Brian Soublet, pointed out, there are a large number of traffic maneuvers – in his words probably too many to test (video). Even worse, there are an unbounded number of driving scenarios – combinations of maneuvers, pedestrians, cars, trucks, motorcycles, cyclists, road geometry, stop signs, traffic lights, weather conditions and more. You can’t road test all of them or even any large fraction because the test space is effectively infinite. The only way to probe them is to examine and audit the source code, and also to run the software through simulators – under the watchful eyes of DMV or third-party experts.

As a teenager, I managed to halt a “crash-proof” computer by directing it to take input from the display screen and send output to the keyboard, both of which were obviously impossible. It was a simple prank that the programmers somehow hadn’t anticipated. What pranks and scenarios will driverless car companies overlook as they turn their machines loose?

Cybersecurity and More

Yesterday’s pranks are today’s cybersecurity threats, of course, and these cars will be vulnerable. Even today, cars are at risk. Yet, John Tillman of Mercedes, Chrysler’s Good and VW’s Wendling all urged the DMV not to regulate driverless car cybersecurity (video). They didn’t feel that DMV was the right agency for the task, but had no alternative proposals.

There will be a lot of pressure for driverless car software upgrades to be transmitted wirelessly over the air (OTA), but this should only be allowed with extraordinary security. OTA mechanisms represent enormous threat vulnerability. Moreover, even under the best of circumstances, software updates are problematic, especially when the initial code is complex. It’s easy to “break something” when you’re in the process of fixing something or adding capabilities. The FDA found that 79 percent of software-related recalls in medical devices were due to defects introduced in updates, not in the original code.

There are also legal issues, because adhering to the Vehicle Code isn’t always straightforward. Soublet highlighted a left turn issue which Google acknowledged ruefully (“I can’t believe you’re bringing that up,” said Medford; video). Soublet also mentioned that obeying the speed limit on a freeway isn’t always the right thing, since it can lead to vehicles traveling too slow for traffic conditions. Here again, the decisions should be made by the DMV, not Google – and certainly not Google alone.

(Other legal issues – who’s liable for accidents, who gets the ticket and the points when a self-driving car breaks a traffic law, how will insurance work – were discussed at the DMV hearings but don’t relate to the point of this article.)

Adding to the seriousness of all of these issues – safety, ethics, privacy, cybersecurity, legal – is software monoculture, or the presence of the same software in many vehicles. This means that failures will affect numerous people, just like a bug in MS Word affects millions of people.

Can we trust Google or car companies to protect our privacy, ensure our safety, guard against bugs, prevent cars from being weaponized into self-driving human-free suicide bombs, make ethical decisions when crashes are unavoidable, and all the rest? No, not without rigorous oversight and meaningful independent certification.

Finally, we also have to put these cars in context. They're the first safer-yet-dangerous autonomous robots the public will encounter. There will be more -- eventually Honda's ASIMO robot will be released from the lab, ATLAS will come untethered and BigDog and other Boston Dynamics (i.e., Google) robots will be set loose, whether as helpers, packbots, monitors, security bots or more. Will we get the same answer then -- "this technology is a net good, regulators are self-interested, auditors wouldn't catch the bugs, so let the company self-certify and be done with it"? Google plays a long game and a large one. They're aware that they may be setting a precedent for the way robots are regulated, or not.

The California DMV regulations – which may set a national and even international template (video) – will be out soon. Hopefully, they’ll be adequate to the task. Click here to tell the DMV what you think (and cc me).

Jonathan Handel (jhandel.com) is an entertainment/technology attorney and journalist in Los Angeles. He does not have clients related to self-driving cars. The opinions expressed here are his own. Images via Wikipedia and do not imply endorsement or affiliation.